Many of the blocks in GNU Radio allow the user to select what data type (complex, float, int, byte, etc.) the block operates on. Writing a new block to handle each data type would be tedious, so the framework includes a utility to generate a number of different blocks from template files. I’ve used this to handle different data types in my message utility blocks and some research projects. While useful, I haven’t seen a lot of out-of-tree projects use it so I thought I’d add a step-by-step guide to using the utility for your own out-of-tree blocks.

Background

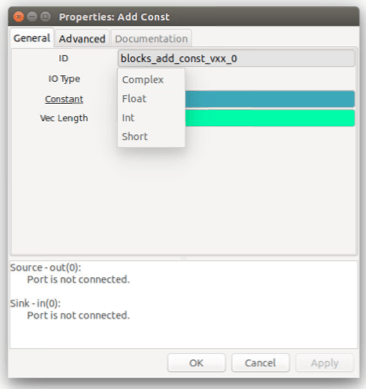

One may notice that many of the blocks in GNU Radio Companion include an option to configure the data type (complex, float, int, byte, etc.) that the block uses, often with a parameter called “IO Type”:

The Add Const block supports several data types

Looking at the relevant parts in the block’s XML definition file we see that the option is used to call a different block for each data type

blocks.add_const_v$(type.fcn)($const)

...

<param>

<name>IO Type</name>

<key>type</key>

<type>enum</type>

<option>

<name>Complex</name>

<key>complex</key>

<opt>const_type:complex_vector</opt>

<opt>fcn:cc</opt>

</option>

<option>

<name>Float</name>

<key>float</key>

<opt>const_type:real_vector</opt>

<opt>fcn:ff</opt>

</option>

...

For example, selecting the complex option causes GNU Radio to call blocks.add_const_vcc whereas the float option will call blocks.add_const_vff. So where are those defined?

Though they are separate blocks in the view of GNU Radio, each was generated from a common file. Looking in the gnuradio/gr-blocks/lib directory we see the files add_const_vXX_impl.cc.t and add_const_vXX_impl.h.t which are the template files for each block. There is a similar add_const_vXX.h.t in the gnuradio/gr-blocks/include/gnuradio/blocks directory. Taking a look at the CMakeLists.txt shows the commands to generate the blocks.

include(GrMiscUtils) GR_EXPAND_X_H(blocks add_const_vXX bb ss ii ff cc)

At compile time, the appropriate files will be generated from the templates and compiled. After that, they can be called from a Python or GNU Radio companion like any other block.

Let’s Build Our Own

There are a few steps to using the utility in your own out-of-tree projects, so let’s go through them step-by-step. Following the steps of the GNU Radio tutorial for writing out-of-tree modules we’ll create a block that performs a simple squaring operation. We’ll go through the process step-by-step, but the end result can be downloaded from GitHub to save some typing.

The new module was created using gr_modtool newmod howtogen. After that, the template files square_XX.h.t, square_XX_impl.cc.t, and square_XX_impl.h.t were added. Let’s take a look at those, beginning with square_XX.h.t:

#ifndef @GUARD_NAME@

#define @GUARD_NAME@

#include <howtogen/api.h>

#include <gnuradio/sync_block.h>

namespace gr {

namespace howtogen {

class HOWTOGEN_API @NAME@ : virtual public gr::sync_block

{

public:

typedef boost::shared_ptr<@NAME@> sptr;

static sptr make();

};

} // namespace howtogen

} // namespace gr

#endif /* @GUARD_NAME@ */

When generating files, the utility will replace @NAME@ with the appropriate class name: square_ff for the float case, square_cc for the complex, and so on. Looking in the work function of square_XX_impl.cc.t we see similar variables:

int

@NAME_IMPL@::work(int noutput_items,

gr_vector_const_void_star &input_items,

gr_vector_void_star &output_items)

{

@I_TYPE@ *in = (@I_TYPE@ *) input_items[0];

@O_TYPE@ *out = (@O_TYPE@ *) output_items[0];

for(int ii=0;ii<noutput_items;ii++)

{

out[ii] = in[ii]*in[ii];

}

return noutput_items;

}

The utility will replace @I_TYPE@ and @O_TYPE@ with the correct data types: byte, int, float, etc. @NAME_IMPL@ will be the same as @NAME@ but with _impl at the end, as in square_ff_impl. To summarize, here is a list of the macros when translated for the float case:

| Template | Expanded |

|---|---|

| @NAME@ | square_ff |

| @NAME_IMPL@ | square_ff_impl |

| @GUARD_NAME@ | INCLUDED_HOWTOGEN_SQUARE_FF_H |

| @I_TYPE@,@O_TYPE@ | float |

An XML file is created that allows the user to call the appropriate block from a user-selectable parameter in GNU Radio. A part of that is shown below:

<make>howtogen.square_$(type.fcn)()</make>

<param>

<name>IO Type</name>

<key>type</key>

<type>enum</type>

<option>

<name>Complex</name>

<key>complex</key>

<opt>fcn:cc</opt>

</option>

...

That gets all our files in place. What’s left to do is instruct the compiler how to expand and install the generated blocks. We’ll edit include/howtogen/CMakeLists.txt:

include(GrMiscUtils)

GR_EXPAND_X_H(howtogen square_XX ss ii ff cc bb)

add_custom_target(howtogen_generated_includes DEPENDS

${generated_includes}

)

install(FILES

api.h

${generated_includes}

DESTINATION include/howtogen

)

GrMiscUtils is included in the make file and the GR_EXPAND_X_H macro tells the module name, the header file template name, and then lists what data types to expand with. These files will be generated as ${generated_includes} so we’ll need to tell CMake to install those. Similar instructions are added to lib/CMakeLists.txt:

include(GrPlatform) #define LIB_SUFFIX

include(GrMiscUtils)

GR_EXPAND_X_CC_H_IMPL(howtogen square_XX ss ii ff cc bb)

include_directories(${Boost_INCLUDE_DIR})

link_directories(${Boost_LIBRARY_DIRS})

list(APPEND howtogen_sources

${generated_sources}

)

set(howtogen_sources "${howtogen_sources}" PARENT_SCOPE)

if(NOT howtogen_sources)

MESSAGE(STATUS "No C++ sources... skipping lib/")

return()

endif(NOT howtogen_sources)

add_library(gnuradio-howtogen SHARED ${howtogen_sources})

add_dependencies(gnuradio-howtogen howtogen_generated_includes howtogen_generated_swigs)

target_link_libraries(gnuradio-howtogen ${Boost_LIBRARIES} ${GNURADIO_ALL_LIBRARIES})

set_target_properties(gnuradio-howtogen PROPERTIES DEFINE_SYMBOL "gnuradio_howtogen_EXPORTS")

We’ll again include GrMiscUtils and use the GR_EXPAND_X_CC_H_IMPL macro to generate the appropriate files. We’ll need to add {$generated_sources}to the sources and finally add howtogen_generated_inlcudes and howtogen_generated_swigs as dependencies using add_depedencies.

The next step is to add the files to howtogen_swig.i. There’s no macro to expand these, so we’ll type in each filename manually.

#define HOWTOGEN_API

%include "gnuradio.i" // the common stuff

%include "howtogen_swig_doc.i"

%{

#include "howtogen/square_bb.h"

#include "howtogen/square_ss.h"

#include "howtogen/square_ii.h"

#include "howtogen/square_ff.h"

#include "howtogen/square_cc.h"

%}

%include "howtogen/square_bb.h"

%include "howtogen/square_ss.h"

%include "howtogen/square_ii.h"

%include "howtogen/square_ff.h"

%include "howtogen/square_cc.h"

GR_SWIG_BLOCK_MAGIC2(howtogen, square_bb);

GR_SWIG_BLOCK_MAGIC2(howtogen, square_ss);

GR_SWIG_BLOCK_MAGIC2(howtogen, square_ii);

GR_SWIG_BLOCK_MAGIC2(howtogen, square_ff);

GR_SWIG_BLOCK_MAGIC2(howtogen, square_cc);

Lastly, we’ll edit the howtogen_swig.i file to include the following lines:

file(GLOB xml_files "*.xml")

install(FILES

${xml_files} DESTINATION share/gnuradio/grc/blocks

)

Now everything should be in place to build. The Git repo contains some unit tests to ensure the square operation performs correctly. There is also a GNU Radio Companion flow graph to test if the XML generation worked correctly.